At the time of writing, Zurich’s most famous department store Manor is closing. U.S. American corporations like JCPenney and Barneys New York are bankrupt, and so is the department store chain Neiman Marcus. What is left of Sears, once the world’s largest retailer, survives on emergency credit. Amazon, for its part, has seen massive increases in revenue in the same period. Hybrid retailers, with a presence both online and on the street, are rapidly trying to adapt their business models. Zara, for instance, may close over a thousand of its shops, even as it sees online sales increase by a half. The department store was already in trouble, not least because of online shopping and the increasing vertical integration of luxury brands. Successful brands, that once vied with each other to be displayed in department stores, now seem hampered by them. The department store, a genre of business that has a continuous history that goes back to the 19th century, is officially toast. This will have consequences.

![]()

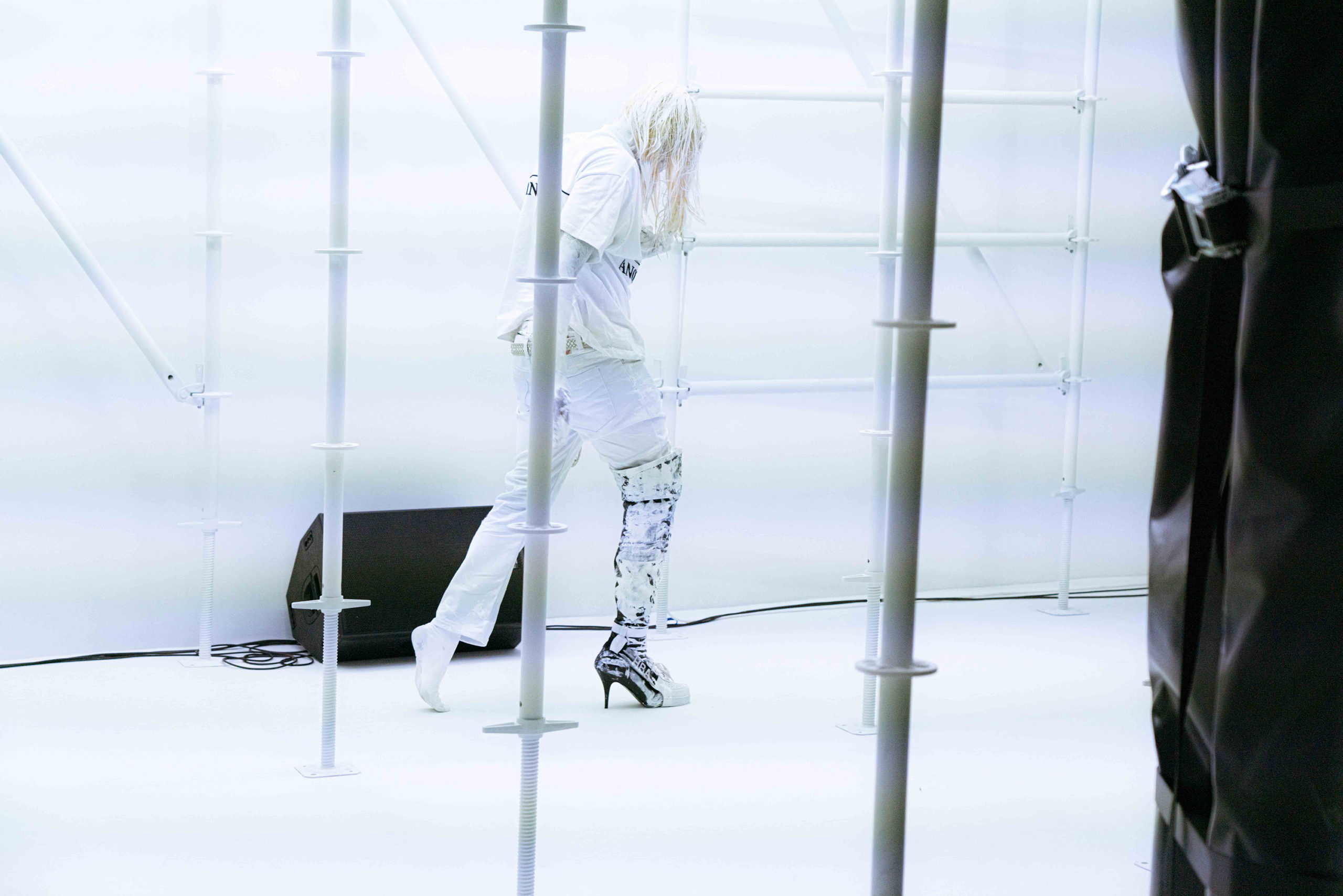

Anonymous Club, Prologue Performances by LEECH I, 2020 Performance direction by Josh Johnson and Boychild, Luma Westbau, Zurich Photo: Jelena Luis

Aside from all the traditional business models, left maimed and dying on the battlefield after Amazon’s victorious global campaign, what will go missing with the end of retail is other shoppers? When we shop in department stores, we see products, but we also see people. The classic moments are perhaps provided by escalators, those post-industrial conveyor belts designed not to speed up production but to foster consumption. Watching people on escalators, carrying their shopping bags, their aspirations, their anxieties, is endlessly entertaining. Other shoppers function as examples. Everything that they wear and carry show a history of past shopping sprees, and we can choose to model ourselves on them, or attempt to differentiate ourselves from them, just as they do with us. You see them, and they see you. That tacit mutual observation is the agora, the market incarnate of consumer democracy. When we shop online, however, the dynamic changes radically. We see products, and the products see us. Thanks to the information that we offer up with each click, we are transparent to the algorithms. But what we no longer see are… other shoppers. At most we see indirect traces of them in the form of product reviews or comments, but these are always at the discretion of the purveyor. In physical shops, the products are blind; in the digital shop, we are.

What is the value of the brute material fact of the dead mall for contemporary architects? What potential does the condition of uselessness offer?

The obsolescence of the shopping mall, ruthlessly defined by its program, offers degrees of freedom for architecture that resemble, or even constitute, a kind of autonomy. In contrast, “flagship stores” remain viable, although not necessarily for shopping per se. They serve as a physical mechanism for building an environment, or rather, a world around a brand. They bear the scars of the gladiatorial struggle to differentiate themselves from each other in the midst of a generic global capitalism. And they allow us to re-imagine the perfect museum.